Tags

Embroidery, Gautam Vazirani, Handloom, India, Natural Dyes, Northeast India, Shefalee Vasudev, Sustainability, Sustainable Fashion, Sustainable Luxury, Taj Magazine, Weaving

Published: Taj Magazine, Volume 2, 2018-19

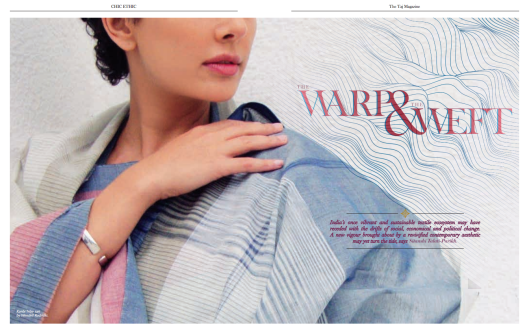

India’s once vibrant and sustainable textile ecosystem may have receded with the drifts of social, economic and political change. A new vigour brought about by a revivified contemporary aesthetic may yet turn the tide, says Sitanshi Talati-Parikh.

The rich texture of thousands of years of Indian culture seeps in like a natural, yet permanent dye in its fabric and woven traditions. It is a symbolic thread that connects the nation in its diversity; perhaps a striking case where tradition marks culture, where craft describes history and where colours speak of the passage of time —of lives lived and memories created.

Weaves, threadwork and textile decoration, among other indigenous crafts spin yarns —even if coloured with the emotions of the artisans — describing the local life. Influenced deeply by the local socio-economic-political environment, but also linked to moments of celebration, like festivals and weddings. The craft, in some cases, has been a rite of passage: a woman decorates her own trousseau that becomes a part of the dowry she takes with her when she gets married.

While over centuries, communities have survived because of their traditional crafts, these have faced erosion in many ways. As Gautam Vazirani, strategist and curator — sustainable fashion at IMG Reliance/ Lakmé Fashion Week, points out, “Many of our local techniques have changed in the last few decades in terms of authenticity of practice, either at the raw material level or in the original process, or in the woven design approach. Only true craft connoisseurs and historians can highlight the state of many languishing crafts today.”

Shefalee Vasudev, the editor of The Voice of Fashion, a digital destination that explores the intersection of fashion and culture, finds that while there are crafts slipping away from us for varied reasons, perhaps not everything needs to be sustained simply because it once existed. She says, “It has to be seen what can be produced, created and have a sense of utilitarian as well as aesthetic value in the contemporary arts and crafts scenario and then sustained or revived.”

The Changing Colours of Dyes

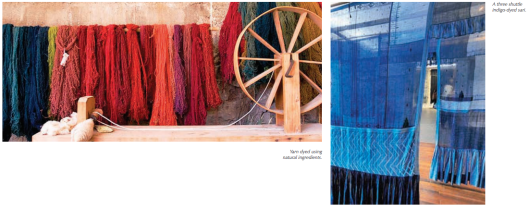

Until the late 19th century, the art of natural dyeing—using natural sources like plants, insects or shellfish—thrived in the Indian subcontinent. Indigo (derived from the indigofera flowering plant) lends itself to the fantastical peacock-plume tones of the country. In the 19th century, Bengal was the world’s main source of indigo. The advent of aniline dyes in 1856 by British scientist William Henry Perkin, and their spread to colonial countries, led to post-independence India no longer retaining its tradition of natural dyes with the exception of a few rural communities.

Revival movements in the 1970s by social reformer and freedom fighter Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and in the 1990s by activist and advocate for craft and natural dyes, Ruby Ghuznavi, initiated the change. But the discovery in 2009 by Dr Himadri Debnath, deputy director of the Botanical Survey of India in Kolkata, of a unique 15-volume set (with 3,500 samples) of Specimens of Fabrics Dyed with Indian Dyes, compiled by British Victorian dyer Thomas Wardle, and believed to have been lost, was pathbreaking to understanding the rich history of natural dyes in India.

Today, conscious designers are willing to pick up the mantle once more. Kolkata-based Maku has brought back the splendour of natural indigo, and brands like Delhi-based 11.11/eleven eleven and Ahmedabad-based Soham Dave only use natural dyes; while Colours of Nature (Auroville) collaborated with Levi’s to launch the first truly organic 511 jeans made with organic indigo dye and local cotton yarn in 2013.

The Art of Fabric Decoration

In contemporary times, industrialised, machine-made versions have largely replaced India’s traditional, rich and varied embroidery forms. The art was popular during the Mughal empire, and Indian floral motifs have influenced British embroidery, including the popular paisley shawls. Colonial demand subsequently led to mass-production and reduction of the handcrafted process which could take months.

Not restricted to garments, forms of embroidery appear on wallhangings, home furnishings, fashion accessories and textiles. Mostly inspired by nature and local life, prints and thread-work would create patterns in vibrant colours often embellished with zari (precious gold or silver thread-work) or varak (precious gold or silver foiling). Genuine varak printing on fabric is very rare today and reportedly there are only two artisans in Jaipur who still practice the art.

As handmade items are reclaimed as new embodiments of luxury, and local runways are reviving many of the handcrafted techniques, many of these old decorative textile styles have been lost forever—like the Tanjore paintings on fabric using precious materials, which have inspired many offshoots but are no longer available in their original form. The Kodali Karuppura saris, created in a small town in Tamil Nadu, mainly for the Thanjavur nobility, have, Vasudev points out, completely vanished. The hand-painted and naturally-dyed textile flourished under the patronage of the Maratha rulers of Tanjore—today, a few samples can be seen in museums in India and abroad.

While designers like Kolkata-based Sabyasachi Mukherjee and Mumbai-based Anita Dongre have taken up the mantle of India’s embroidery tradition—Dongre has found a way to contemporarise it with brocade dresses and traditional embroidery on western silhouettes—the local craft has also found glamour on international runways. Belgian couturier Dries van Noten has had an embroidery workshop in Kolkata since 1987, while brands like Valentino, Gucci, Givenchy, Balmain, Ralph Lauren and Christian Dior, among many others, work with Mumbai-based trade embroidery companies to this day.

The gara style of embroidery on traditional Parsi saris had been losing popularity and been replaced by machine-made versions—due in part to the diminishing Parsi community and the painstaking process—until there was a renewed interest in the form, along with its use on accessories and the modernizing efforts by designers like Ashdeen Lilaowala. Even as insurgency hit the supply of local craft, Srinagarand-Delhi-based Kashmir Loom by Asaf Ali and Jenny Housego has, successfully contemporized their traditional handwork on cashmere shawls, by incorporating global colours and designs with the age-old techniques, in what they state is, “Preserving heritage while fostering its progress.”

The art of Kalamkari (drawing with a pen) includes stories and mythological tales told on fabric using natural dyes. Kolkata-based designer, Divya Sheth, brings back nature-inspired kalamkari work on her runway pieces.

Sheth says of the experience, “I have had the chance to witness the joy and ease with which the artisans create their masterpieces. The ladies start painting once they complete their daily chores.”

Handloom Tales

With minister of textiles, Smriti Irani, throwing her support behind Indian handlooms, and the shutterbugs catching the likes of Indian cinema veterans Kangana Ranaut, Sonam Kapoor and Vidya Balan in handloom saris, one accepts that the loom is in focus again and this time, not with the elements that defined the ‘Khadi’ look.

The charkha, or the handloom spinning wheel has a strong symbolic element: while it suggests economic empowerment, it is also an element of the country’s freedom struggle representing self-sufficiency, as well as unity and alliance—it forms the crux between an ecosystem of farmers, weavers, distributors, and consumers.

Among the nomads of Ladakh or in the hills of Kashmir, life and the act of weaving are deeply linked. For instance, in Ladakh, the woven cloth is linked to the birth of a child, where the warp (representing the man) and the weft (the woman) in harmony lead to the creation of new life. And yet, there is a long way to go for the new lease of life of the handloom garment.

Today, Indian artisans are facing a tremendous challenge from the advent of the power loom and machine-made garments. For instance, much of the famous Kota Doria textile in Kota, Rajasthan, is being woven without the real sari (that was a signature material) and the fabric itself is being made in power loom and not in the traditional handloom (for commercial reasons). However, as Vazirani points out, Craftmark’s initiative with Kota Women Weavers is in the process of reviving traditional weaving techniques with genuine materials.

Tribal textiles have been impacted, and consequently the local economy. Vazirani, who has worked extensively in the north-eastern region of India, points out that there has been a shift to acrylic yarns and fabric for weaving instead of cotton, silk and wool yarns, with a mutation of woven designs due to changes in cultural, economic and environmental conditions.

Vasudev brings up techniques that may be lost, like the painstaking Dakmanda weave of the Garo tribe in Meghalaya. Even as the industry in the North East has the highest concentration of handlooms in the country—over 53 percent of looms and more than 50 percent of the weavers live in this region—it is fraught with challenges including poor supply chain management.

Vazirani says, “There is a good opportunity to address the challenges and find sustainable solutions through the Action Plan on North-East India Report—an initiative in partnership with the United Nations in India and IMG Reliance—for the mainstream industry.” And as handloom hits the runway, one may also credit the persistent and long-standing efforts of conscious designers.

For instance, designers like New Delhi-based Rajesh Pratap Singh revert to the old traditional techniques—setting up the loom to make the garment and weaving it from the start. In fact, when Singh’s looms are empty, he uses it to make saris to ensure sustainability not only of craft and thread but also of the iconic garment. Designers like Delhi-based David Abraham and Rakesh Thakore of label Abraham & Thakore and Rahul Misra; as well as labels like Bodice, which won the 2017/18 International Woolmark prize for womenswear, and Raw Mango are among the many designers adopting handmade textiles and handcrafted garments. Misra’s motto is clear on his website: “My objective is to create jobs which help people in their own villages, I take work to them rather than calling them to work for me. If villages are stronger you will have a stronger country, a stronger nation, and a stronger world.”

The Frugality of Fashion

An intrinsic part of indigenous craft used to be the considered use of materials. Cyclical production was a part of the natural ethos of the communities, as what was made was in direct relation to demand. In India, such thrift is not new: saris and dupattas are used in the manner in which they come off the loom, while designs like ponchos and kalidar clothes are constructed keeping the wastage of fabric to a minimum.

And yet, today, approximately 120 billion square metres of fabric end up as waste in India, China and Bangladesh alone, not including garment rejections during quality checks. Knowing this, Delhi-based Kriti Tula of label Doodlage says she upcycles up to 600 kilograms of waste fabric every month. Designers like Karishma Shahani Khan, the founder of Pune-based label Ka-Sha, in her ‘Heart to Haat’ ideology works with her own scrap and that of industry friends’ material in footwear, stuffed toys, embroidery, patchwork, macramé and bags.

The State of Workers

While sustainability in terms of keeping craft and knowledge and enterprise alive is important—we are constantly reminded of Mahatma Gandhi’s words: “There is no beauty in the finest cloth if it makes hunger and unhappiness.” A year-long research project called the Garment Worker Diaries that included field study in Bengaluru, India, reported on the sorry state of the garment workers; mostly women.

Long hours, being forced to do more work than their allotted quota, lower pay and verbal abuse were unveiled in the report. In 2013, the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh—which housed five garment factories supplying global brands—saw the death of 1138 people while 2500 were injured, which should be a sufficient wake-up call for the fashion industry.

Today, designers are reportedly making attempts to work directly with cooperatives, like Mumbai-based brand Kishmish with NGO Kala Swaraj and designer Samant Chauhan for the cause of master weavers in his native Bhagalpur, in Bihar. Reportedly, Gaurang Shah works with over 700 weavers across India and The Goodloom by GOCOOP enables a direct connection between handloom cooperatives and artisans. There is a growing, if nascent, push towards better labour and environmental standards and more transparent supply chains, with the advent of global organizations like Fashion Revolution in India.

Demand and Supply

Vasudev points out that the general awareness of what sustainability in fashion means is very poor, and it slants merely towards that which is organic and natural. She believes that to say India is realigning itself towards sustainability would be a premature remark because the masses are not aligned with it. “The sustainability manifestos are lost; they have to be brought together and pushed in a contemporary format and I do not see that happening very much, even as the sustainability argument is staggered with clued-in fashion designers and manufacturers,” says Vasudev.

While it hasn’t reached mainstream consumption, consciousness is growing among a certain audience, as awareness continues to increase. Niche retailers like Paper Boat Collective in Goa, Toile in Mumbai and pan-India brands like Good Earth Sustain and Nicobar make attempts in individual ways to be mindful— in choice of products, materials and packaging. The Auroville market in Pondicherry supports a sustainable ethic—supply and demand work in tandem with mindfully crafted goods versus mass-produced ones.

And so, we may hope that more people begin to lean towards what Vazirani strives for: “An awakening and appreciation of the wealth we have in our country in terms of our artisans and the beautiful textiles that they are capable of weaving without any luxury facilities or formal education. An understanding of who we are, when we say Indian fashion, and establishing our own independent sense of style. It is feeling of pride in wearing the Khadi shirt, or the handwoven Indigo-dyed dress, or the Dabu hand-printed saree instead of a Western high-street outfit. Nowhere in the world can we get access to the luxury of genuine handmade as we still do in India.”

We can also work toward a socially conscious and sustainable fashion ethic so that Indian fashion undergoes a shift towards what Vazirani calls a “fashion consciousness—where what you wear makes a commitment to a higher ideal beyond its hanger value or glamour.”

Link to PDF of the story. The Warp and the Weft – Taj Magazine 2019

Padmaja

Padmaja